In a decisive shift away from the stark, clean lines of minimalist design, a growing movement is embracing the warm, personal clutter of memory-filled homes. Writer Eleanor Burnard declares herself a champion of this trend, arguing that a space brimming with personal history offers a powerful antidote to modern sadness.

The Heart of a Sentimental Maximalist

Burnard openly admits to being intensely sentimental. Her home is a carefully curated archive of her life, filled with objects others might discard. Old birthday cards, faded stuffed toys, and handmade gifts from former friends all have a permanent place. Each item has a story: a hot-pink alpaca won on a first try at a Japanese arcade a decade ago, a coffee-stained Matisse print rescued from the roadside with a first roommate, and a treasured One Direction tour T-shirt that remains in weekly rotation.

Her style, which she terms sentimental maximalism, includes recent additions like Sylvanian Families figures and beloved hand-me-downs such as her grandmother's ceramic ram. While some might see the early signs of a hoarding problem, for Burnard and her generation, these collections represent something far more profound.

Nostalgia as a Lifeline in Uncertain Times

This embrace of trinkets is seen as a generational response to economic instability and the pressures of adulthood. Faced with an uncertain future, many are finding comfort and identity in the tangible past. The whimsical, saccharine nature of these collections creates a joyful environment that consciously counters gloom.

However, the relationship with these objects is complex. Not every memento sparks pure joy; some bring pangs of heartache for lost connections or waves of cringe over past phases, like dusty anime figurines or a framed picture of Lana Del Rey from a 'stan Twitter' era. Yet, even these embarrassing artefacts are cherished for marking who she was.

More Than Dust: Trinkets as Tangible Memory

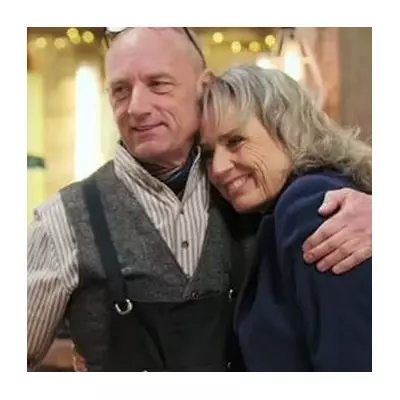

For Burnard, these possessions form a physical mosaic of her life's journey and relationships. While social media offers a digital memory lane, there is a unique magic in being able to physically touch and interact with the past. This philosophy is shared by her mother, who keeps a small amber glass bird from a friend who died in the 1970s, a tether to that memory across decades and international moves.

The emotional weight of this practice is poignantly illustrated by a Hello Kitty birthday card from a close friend, given to Burnard when she turned 16. The friend was killed the following year, and the card remains a cherished, tangible piece of her that Burnard revisits. These objects are not mere novelties; they are vessels for the people we have loved and the selves we have been.

Ultimately, the trend towards sentimental maximalism is a rejection of impersonal austerity. It is a deliberate choice to surround oneself with the layered, sometimes messy, but always meaningful evidence of a life fully lived, proving that a home can be a sanctuary of memory as much as a place of rest.