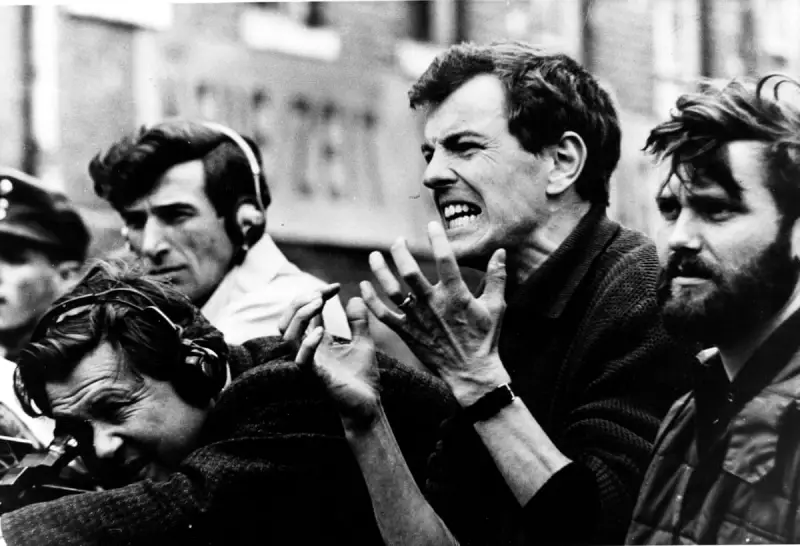

The name Peter Watkins may not be as widely recognised as some of Britain's cinematic giants, but his impact on documentary film-making remains profound and unsettling. This visionary director, now approaching his ninth decade, created works so revolutionary that they shook the establishment to its core.

The Battle That Changed Television

In 1964, Watkins unleashed 'Culloden' upon an unsuspecting BBC audience. This groundbreaking film depicted the 1746 Jacobite defeat with brutal authenticity, using techniques that would become his signature style. Rather than traditional historical documentary, Watkins employed newsreel-style reporting, interviewing 'contemporary' participants as if cameras had been present at the battle.

'Culloden' wasn't merely educational television—it was an emotional assault. Viewers witnessed the Highland clearances and battlefield brutality with unprecedented immediacy. The film's power lay in its ability to make historical tragedy feel terrifyingly present.

The Film That Shook the BBC

If 'Culloden' was revolutionary, Watkins' follow-up was seismic. 'The War Game', his 1965 depiction of nuclear attack on Britain, proved so disturbing that the BBC suppressed it for twenty years. The corporation claimed the film was 'too horrifying for the medium of broadcasting,' though many suspected political motivations.

Despite the ban—or perhaps because of it—'The War Game' won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature in 1966. The irony was palpable: a film deemed too disturbing for British television had triumphed on cinema's biggest stage.

American Exile and Radical Visions

Watkins' uncompromising approach eventually led him abroad. His 1971 film 'Punishment Park' presented a dystopian America where political dissidents faced brutal treatment in desert concentration camps. The film's mockumentary style, featuring improvised dialogue and handheld cameras, created such verisimilitude that it remains deeply unsettling decades later.

This self-imposed exile marked the beginning of Watkins' lifelong critique of what he termed the 'Monoform'—the standardised, hierarchical approach to media that he believes suppresses meaningful discourse.

A Legacy of Resistance

Now living quietly in France, Watkins continues to advocate for media reform through his website and writings. His films, once controversial and suppressed, are now studied in film schools worldwide as masterclasses in political cinema.

What makes Watkins' work endure isn't just its technical innovation, but its moral courage. At a time when documentary was largely decorative, he weaponised the form, forcing audiences to confront uncomfortable truths about power, violence, and complicity.

As one contemporary filmmaker noted, 'Watkins didn't just make films about history—he made history with his films.' His legacy serves as a powerful reminder that the most important art often emerges from challenging, rather than comforting, its audience.