The celebrated legacy of neurologist and author Oliver Sacks has been called into question following startling revelations that he fabricated details about his psychiatric patients, at times to alleviate his own 'boredom'. A new investigation by The New Yorker, a publication to which Sacks was a frequent contributor, has unearthed admissions from his private journals that some of his most famous non-fiction case studies were embellished or entirely invented.

The 'Fairy Tales' in a Medical Classic

Central to the controversy is Sacks's bestselling 1985 work, The Man Who Mistook His Wife For A Hat, a book lauded for bringing humanity to complex neurological disorders. Discover magazine ranked it among the 25 greatest science books of all time in 2006. However, the new report reveals the patient's wife in the titular story 'privately disagreed' with Sacks's dramatic depiction of her husband attempting to lift her head off and place it on his own.

Another story in the same book, featuring autistic twins with extraordinary calculative abilities, was described by Sacks in his diaries as the 'most flagrant example' of his distortions. He confessed the account was inspired by his own childhood spent devising formulas for prime numbers, rather than a strictly factual case study.

A Legacy Built on 'Symbolic Autobiography'

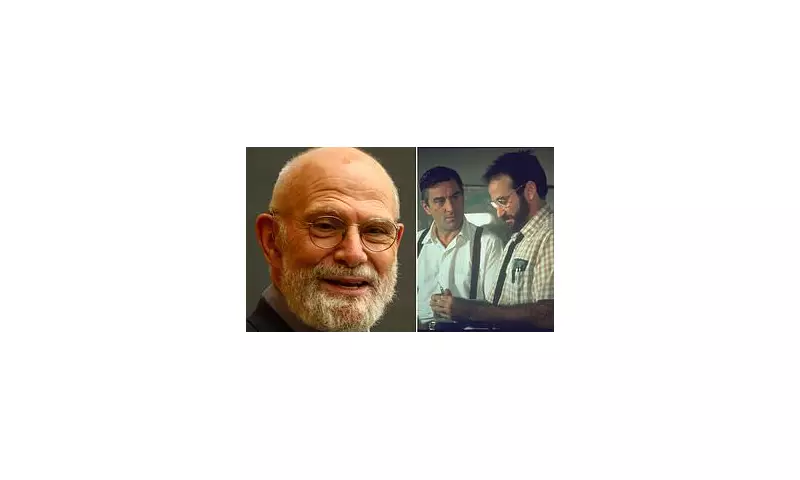

Sacks, who was born in London, educated at Oxford, and later emigrated to New York, where he died in August 2015 aged 82, achieved global fame. His 1973 book Awakenings was adapted into an Oscar-nominated 1990 film starring Robert De Niro and Robin Williams. Despite this acclaim, his journals paint a picture of a writer who saw his work as 'symbolic autobiography'.

He admitted to giving patients 'powers (starting with powers of speech) which they do not have' and described some accounts as 'pure fabrications'. In a letter to his brother, he framed his narratives as 'half-report, half-imagined, half-science, half-fable', created to keep his 'demons of boredom and loneliness and despair away'. Following the success of The Man Who Mistook His Wife For A Hat, he wrote of increased guilt 'because of (among other things) my lies, falsification.'

Complex Reactions and Enduring Impact

The revelations present a profound ethical dilemma, contrasting the author's self-confessed embellishments with the positive impact his work had on public understanding of neurology. The New Yorker notes that most patients and their families were largely happy with their portrayals. Renowned scientist Temple Grandin, whose autism was detailed in Sacks's 1995 book An Anthropologist on Mars, defended him, stating he 'got inside my emotions in a way that other people hadn't.'

However, critics during his lifetime accused him of exploitation, with one academic branding him 'the man who mistook his patients for a literary career'. The new evidence from his private papers adds significant weight to these longstanding concerns, forcing a re-evaluation of where empathetic storytelling ends and fabrication begins in popular science writing.

The story emerges alongside a separate scandal involving another bestselling UK author, Raynor Winn (The Salt Path), who has been accused in a recent documentary of stealing £64,000 from a former employer, allegations she disputes. Both cases highlight the intense scrutiny facing authors whose lucrative memoirs and non-fiction narratives are challenged.