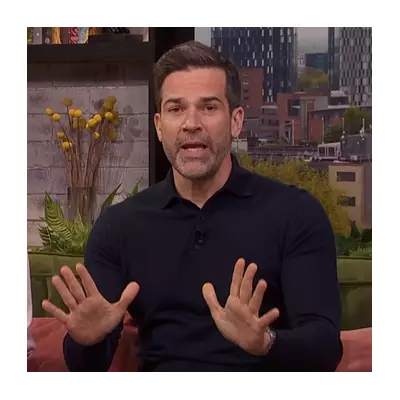

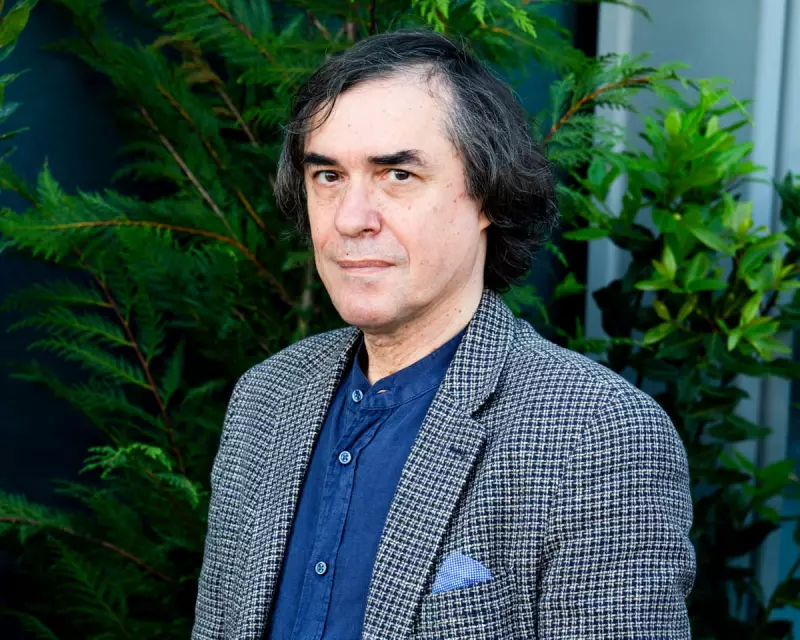

Romanian literary sensation Mircea Cărtărescu has finally brought his monumental Blinding trilogy to British readers, nearly three decades after its initial publication in his native language. The acclaimed author opens up about his complex relationship with communism, his father's political disillusionment, and the literary revenge that fuels his surreal masterpiece.

From Butterfly Dreams to Literary Stardom

In 2014, Cărtărescu fulfilled a lifelong dream during his American book tour: visiting Vladimir Nabokov's butterfly collection at Harvard. The Romanian writer shares more than just Nobel Prize speculation with his Russian-American idol – both possess a profound fascination with lepidopterology that deeply influences their work.

"His most important scientific work was about butterflies' sexual organs, and I saw these very tiny vials with them in," Cărtărescu recalls with visible awe. "It's like an image from a poem or a story. It was absolutely fantastic."

This enchantment with butterflies forms the structural backbone of Blinding, which critics voted Romania's novel of the decade in 2010. The trilogy is conceived as a butterfly in shape, with the first and third parts representing wings and the middle book serving as the body.

Surreal Visions and Political Reckoning

The Left Wing, now published by Penguin Classics in the UK, blends memoir with dreamscape in a style that distinguishes Cărtărescu from his literary hero Nabokov. While both share scientific curiosity about butterflies, the Romanian author ventures into territory Nabokov avoided – the fantastical and surreal.

One particularly striking scene depicts medieval villagers discovering gigantic butterflies frozen beneath the Danube's ice, "20 paces long and 40 paces wide." After marvelling at their beauty, the villagers proceed to hack away the ice and boil the creatures like lobsters for a sumptuous feast.

"Nabokov was a fine artist, but he had fewer connections with fantastical literature and surrealism than I have," Cărtărescu explains from his Bucharest flat. "The image of the huge butterflies under the ice of the Danube could have come from Salvador Dalí."

The trilogy has been compared to James Joyce's Ulysses for its transformative portrayal of Bucharest, though Cărtărescu's vision is far from sentimental. His narrator imagines the city's bronze statues descending from plinths to copulate with limestone gorgons, while a tower block appears as "the city's penis, red and erect."

This isn't a love letter to his birthplace but rather "a stylistic and literary revenge against the people who stole my youth."

A Family Divided by Political Change

Born in June 1956, Cărtărescu grew up within Romania's communist regime, which maintained a notoriously non-docile status within the Soviet sphere. His father, who features prominently in the trilogy's Swiftian third part, actively participated in the communist administration.

The 1989 revolution created a painful schism within the family. When news spread of President Nicolae Ceaușescu fleeing by helicopter, Cărtărescu witnessed his father's political world collapse.

"He went to the kitchen and put his red party book on the fire," the author remembers. "He was crying all the time because he believed in communism and now he saw that everything was a lie."

While his father mourned the system's collapse, the younger Cărtărescu felt liberated. As part of the beatnik-influenced "blue jeans generation" – who wore primitive Romanian-made denim and memorised Allen Ginsberg's Howl – the revolution opened new horizons.

"After the revolution I became a citizen of the universe," he reflects. Having spent approximately one-third of his post-Cold War life abroad, he wrote most of the 1,400-page Blinding trilogy outside Romania, completing it over fourteen years in Amsterdam, Berlin, Budapest and Stuttgart.

International Recognition and Nobel Speculation

Recent years have seen Cărtărescu's work achieve the universal status he aspires toward. His novel Solenoid earned International Booker longlisting this year, while German magazine Der Spiegel included The Left Wing among the world's 100 best books. A new French translation also appeared this year.

His consistent presence in Nobel Prize conversations for the past decade has undoubtedly boosted his international profile. In both 2023 and 2025, bookmakers placed his odds at 11/1 – comparable to his idol Thomas Pynchon.

"I never waited for a call," Cărtărescu insists about the Nobel speculation. "I'm grateful to the people who consider me worthy of it, because to be seen as worthy of the Nobel prize, even if it's only a rumour, is an absolute honour."

This year's award going to Hungarian author László Krasznahorkai might temporarily dampen his chances, given the Swedish Academy's potential reluctance to honour another Eastern European writer consecutively. Nevertheless, Cărtărescu proudly identifies with the current "boom of eastern writers" comparable to the Latin American literary explosion of the 1960s and 70s.

He attributes Eastern European writing's freshness to its non-commercial spirit: "They never thought of making money or getting prizes; they were people who really loved literature. They are totally devoted to their art."

Complex Romanian Identity and Religious Awakening

Despite his international perspective, distinctly Romanian elements permeate Cărtărescu's work, particularly regarding religion. Growing up under communism meant "we never went to church and we didn't have a Bible in our home." Until age thirty, he believed the Bible was merely "a collection of sermons."

Unlike other former Eastern bloc nations that embraced secularism, Romania witnessed a religious resurgence, with over 73% identifying as Orthodox Christian in the 2021 census. When someone finally gave Cărtărescu a Bible, his perspective transformed completely.

"I was reluctant to look through it, but when I started reading I couldn't stop," he admits. "I noticed it wasn't just a holy book but the greatest novel ever written."

This religious awakening manifests strikingly in The Left Wing through an epic battle between angels with double-edged swords and horned "cacodemons," with monsters eventually driven back by angelic psalms.

Cărtărescu's ambivalent relationship with his homeland reflects broader Romanian contradictions. While Romania boasts the EU's largest diaspora – 3.1 million citizens living abroad – many expats recently supported nativist, Maga-esque political candidates.

"For some time, the diaspora were the most democratic and most advanced people, but to our huge surprise they turned completely against it," he observes. "They started to envy the Romanians who lived in Romania when they began earning more money than them abroad."

Despite these challenges, Cărtărescu maintains that "Romanians have always been Europeans and will continue to be," describing EU membership in 2007 as "the most important day in our history."

As Blinding: The Left Wing finally reaches British readers in Sean Cotter's translation, Cărtărescu's unique blend of surreal imagination, political reckoning, and profound humanity offers British literature enthusiasts a compelling gateway into contemporary Eastern European writing.