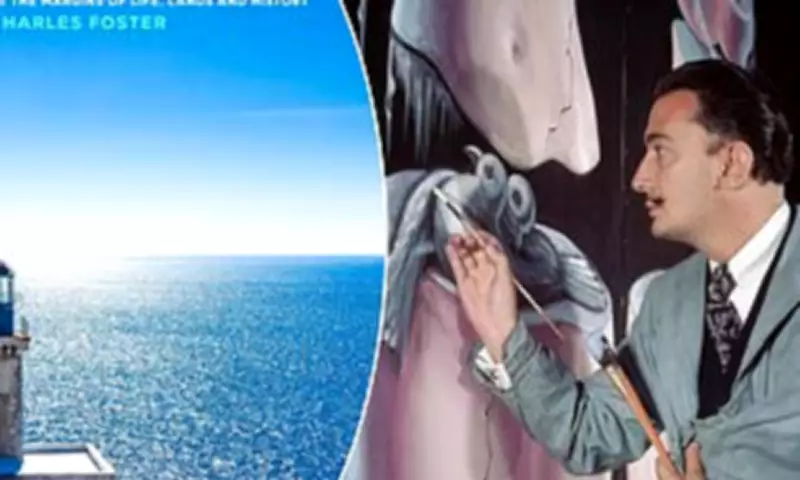

For a profound insight into the surreal and dreamlike paintings of Salvador Dali, one must examine his unusual preparatory ritual. The Spanish artist would sit in a chair, deliberately holding a large key above a metal bowl, and allow himself to drift into sleep. As soon as he nodded off, the key would clatter noisily into the bowl, abruptly waking him. This clever technique enabled Dali to access the fleeting thoughts and images he had just encountered in the hypnagogic state, that curious and fertile territory between full wakefulness and deep sleep.

Pushing Boundaries: Dali's Creative Edge

The trick, as described by author Foster, allowed Dali to discover "the images we all seem to recognise: images that are strange but strangely familiar." This serves as a perfect illustration of Foster's central theory that our very best ideas consistently emerge when we find ourselves on the edge. This could be the edge of consciousness, a physical or geographical boundary, a transitional evolutionary period, or even the fringe of a political movement. Foster demonstrates a clear fascination with edges and peripheries, while expressing a distinct dislike for centres and cores.

A Childhood on the Periphery

Perhaps this perspective is only natural for someone who grew up on the literal edge of Sheffield. Foster recalls, "Our suburban road ran uphill from our house to the wilderness . . . the city twinkling on one side and the moors black on the other . . . I slept always with the windows open, because I wanted the wild in my bedroom." This early experience of living between the urban and the wild seems to have fundamentally shaped his worldview.

Centres Versus Edges: A Cultural Debate

Even when considering the great cities at the heart of historic empires, Foster is quick to dismiss their core achievements. He argues, "Geographical centres are magnets . . . They are chatrooms where edges meet . . . They contribute little to the debate." He points out, for example, that many significant figures in ancient Rome actually originated from the provinces, not the capital itself.

Foster's argument that global hubs like London, New York, and Paris are predominantly populated by people from elsewhere is certainly compelling and difficult to deny. However, one might counter that these individuals are drawn to such centres precisely because they perceive something lacking in their own 'Elsewhere'. People from smaller towns seeking excitement, opportunity, and transformation have historically migrated to London, inevitably changing both themselves and the city in the process. Even if their stay is not permanent, the great metropolis leaves an indelible mark.

The Truth in the Middle: A Personal Reflection

As is often the case, the truth likely resides somewhere in the middle ground. One might reflect on loving city life in London during one's twenties and thirties, and then equally cherishing a subsequent life in rural Suffolk. Regular visits to the capital can become a weekly treat, appreciated all the more precisely because one no longer resides there. This dynamic suggests that the centre and the edge fundamentally need each other; they exist in a symbiotic relationship.

Edges in Evolution and Behaviour

Foster extends his 'edge theory' to the very process of evolution itself. He posits that progress depends on edges—creatures must mate with others on the extreme periphery of their group, those who are genetically different. A basic biological manifestation of this can be observed in human behaviour, where 'sexual disinhibition' is notably more common on holiday than in the familiar setting of home. It is a little-known fact that British sexual health clinics typically experience a significant surge in business following major holiday periods. It is a perspective that might forever alter one's view of a seaside town like Skegness.

A Challenging but Rewarding Read

It must be noted that Foster's book, The Edges of the World, is not the easiest of reads. The author has a tendency to employ seven words where three might suffice, often favouring complex vocabulary such as 'liminal' and 'metastasis'. Despite this stylistic density, he makes a plethora of fascinating and thought-provoking points. Readers will learn intriguing snippets along the way—for instance, that the word 'ecstasy' literally means 'standing outside yourself', and that the fictional valet Jeeves (of Jeeves and Wooster fame) chose to take his holidays in the Kentish coastal town of Herne Bay.