Archaeologists have pieced together the hidden narrative behind a ‘remarkable’ Roman mosaic discovered in a Rutland field, revealing it illustrates a version of the Trojan War thought lost to history for centuries.

A Discovery That Changed Perspectives

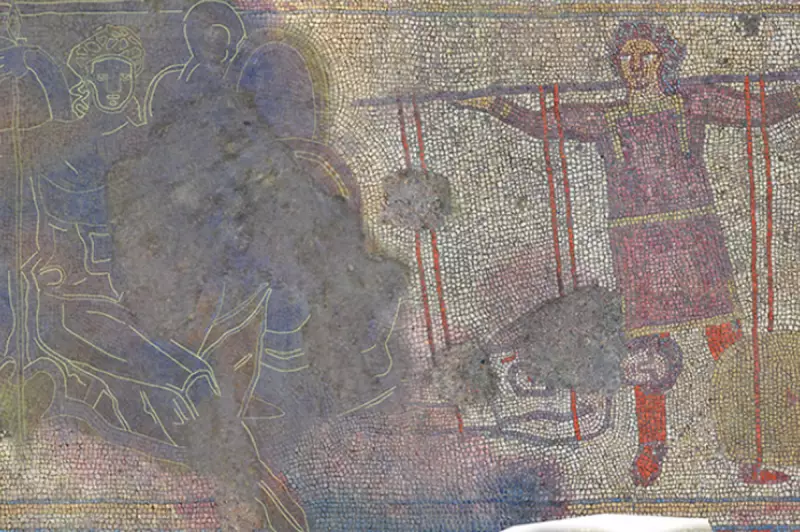

First unearthed in 2020 during an excavation on a farmer’s land near Ketton, the intricate floor was immediately hailed as one of the most significant mosaic finds ever made in the UK. Initial analysis suggested it depicted famous scenes from Homer’s Iliad, but a groundbreaking new study from the University of Leicester has completely transformed that understanding.

The research, led by Dr Jane Masséglia, Associate Professor in Ancient History, confirms the three dramatic panels do show the Trojan War, but not as Homer told it. Instead, they visualise a ‘long-lost’ version of the epic first popularised by the ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus.

Scenes from a Forgotten Epic

The mosaic’s panels, which formed the lavish floor of a dining room in a third or fourth century AD villa, portray a specific sequence from this alternative telling. They show the duel between the Greek hero Achilles and the Trojan prince Hector, the brutal dragging of Hector’s body behind Achilles’ chariot, and finally, the emotional moment King Priam ransoms his son’s body, weighing it against gold.

“In the Ketton Mosaic, not only have we got scenes telling the Aeschylus version of the story, but the top panel is actually based on a design used on a Greek pot that dates from the time of Aeschylus, 800 years before the mosaic was laid,” explained Dr Masséglia.

A Window into a Cosmopolitan Roman Britain

The study’s implications stretch far beyond identifying a story. It provides compelling evidence for the sophisticated cultural connections enjoyed by Roman Britain. Dr Masséglia’s team found that other parts of the mosaic were based on designs traceable to much older artefacts from Greece, Turkey, and Gaul, including silverware, coins, and pottery.

“Romano-British craftspeople weren’t isolated from the rest of the ancient world,” she stated, “but were part of this wider network of trades passing their pattern catalogues down the generations. At Ketton, we’ve got Roman British craftsmanship but a Mediterranean heritage of design.”

Jim Irvine, who made the initial discovery on his family farm, said the research uncovers “a level of cultural integration across the Roman world that we’re only just beginning to appreciate.” He added, “It’s a fascinating and important development that suggests Roman Britain may have been far more cosmopolitan than we often imagine.”

The revelation transforms the Ketton mosaic from a stunning archaeological find into a direct testament to the flow of ideas, art, and mythology across the vast Roman Empire, right into the heart of the British countryside.