A historical execution method so brutal its very name evokes unimaginable horror, Lingchi, known colloquially as 'death by a thousand cuts' or 'slow slicing', represents one of the most gruesome chapters in penal history. Reserved for crimes deemed the most heinous, including treason, this practice involved the prolonged, methodical removal of a condemned person's body parts until death finally intervened.

The Mechanics of a Slow and Painful Death

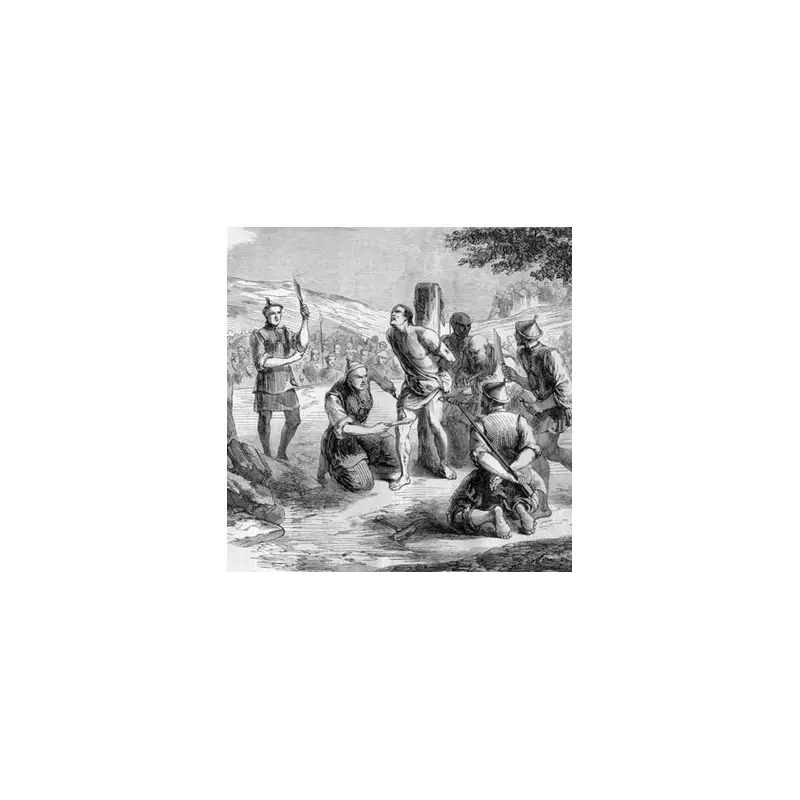

The terrifying procedure was a public spectacle designed to inflict maximum suffering and humiliation. Convicted criminals would be tied to a wooden frame in a public area. Executioners, wielding knives, would then carefully and slowly cut flesh from the body. The law provided no strict limitations on the technique, allowing those carrying out the sentence considerable discretion in prolonging the agony.

This was not merely an execution; it was a form of ritualised torture. The process aimed to cause immense physical pain over an extended period. Furthermore, the punishment extended beyond death itself, as the mutilated corpse would often be left on display for public gawking. Some historical accounts even suggest that flesh from the victims was sometimes sold for use in traditional medicine.

Notable Cases and Historical Context

The practice was not confined to China; it was also used in Vietnam and Korea. It was eventually banned in 1905, but not before claiming many lives. One of the last documented cases was the execution of Wang Weiqin in 1904. The former official, who had murdered two families, was put to death at the Caishikou execution ground in Beijing as punishment for treason and crimes against the family.

Lingchi did not discriminate by gender. A report in the Peking Gazette in 1879 detailed the case of a woman and her lover who were sentenced after killing her father-in-law to conceal their affair. The woman was executed by lingchi. Her husband was subjected to public humiliation using a cangue—a heavy wooden device—as a form of shaming for his perceived lack of control over his wife.

Other alleged victims included figures of significant status, such as Cao Jixiang, a powerful eunuch executed for leading a rebellion, and Yuan Chonghuan, a famed general during the reign of the Chongzhen Emperor, who was rumoured to have attempted a revolt.

A Legacy of Horror in Media and Memory

Although outlawed over a century ago, the visceral horror of lingchi has ensured its place in cultural memory. Its unique and torturous methods have been depicted in various forms of media, from literature to film, often serving as a stark symbol of extreme cruelty and absolute power. The practice stands as a grim historical reminder of the lengths to which judicial punishment has sometimes been taken in the name of justice and deterrence, combining physical annihilation with profound public shaming in what was arguably one of the worst deaths imaginable.