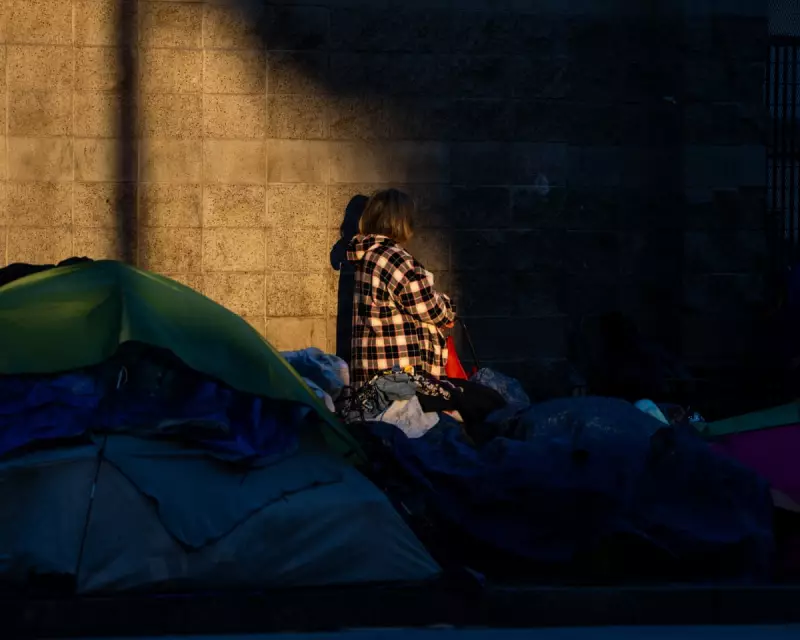

Homelessness advocates across the United States are sounding the alarm, warning that recent sweeping changes to federal housing policy by the Trump administration are 'counterintuitive and dangerous' and threaten to put tens of thousands of vulnerable people back on the streets.

A Lifeline Under Threat

The controversy centres on the Department of Housing and Urban Development's (HUD) flagship Continuum of Care (CoC) programme, a federal initiative that funds housing and support services for individuals at risk of or experiencing homelessness. For Shawn Pleasants, 58, the programme was a lifeline. After a decade living on the streets of Los Angeles's Koreatown, he and his husband received a housing voucher that secured them an apartment, where they have lived for the past six years.

"That feeling of, you could never be safe – there's no more future," Pleasants recalled of his time without a home. The programme, built on the 'Housing First' principle of providing stable accommodation as a foundation for addressing other challenges, has helped over 100,000 Americans like him.

Policy Chaos and Confusion

In recent months, however, the Trump administration has attempted a radical overhaul of the CoC system. The initial changes, announced in November, sought to redirect the majority of the programme's $4 billion in annual funds away from permanent housing towards temporary shelters. Applications would only be allowed to spend 30% of grants on permanent housing, a dramatic drop from approximately 90%.

Internal HUD documents obtained by Politico suggested this shift could leave 117,000 people nationwide without supportive housing. HUD spokesperson Matthew J Maley defended the move at the time, stating, "Housing-first is clearly not working in California or the rest of the country," and calling previous funding a "Biden-era slush fund."

The new policy also mandated treatment for recipients and penalised jurisdictions employing harm-reduction strategies or recognising transgender individuals. These restrictions were rolled back in December, just before federal court hearings. Subsequently, several court orders temporarily blocked the funding overhauls, instructing HUD to process 2025 project applications but not compelling it to award funds.

Amanda Wehrman of the non-profit Homebase described the situation as a "massively chaotic and disruptive moment" for service providers, creating widespread uncertainty about future funding and strategic planning.

Evidence Versus Ideology in the Homelessness Crisis

Experts strongly dispute HUD's assertion that Housing First has failed. Dr Margot Kushel, director of the Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative at UCSF, who conducted a comprehensive study of homelessness in California, stated the cause is unequivocally a lack of affordable housing. To abandon the evidence-based strategy would be "just silly, counterintuitive and dangerous," she argued.

Jonathan Russell, director of Alameda County's housing and homelessness services, oversees 47 CoC grants worth about $60 million. He spent November and December scrambling to cover a $33 million shortfall caused by the policy shift. He contends that permanent supportive housing is far more cost-effective than shelters or street-based services.

- In California, permanent supportive housing costs $20,000 to $25,000 per person annually.

- A shelter bed costs $40,000 to $50,000 per year.

- Leaving someone with complex needs on the street can cost the system $75,000 to $80,000 due to emergency service use.

Russell compared blaming Housing First for not solving homelessness to "blaming alternative energies for failing to mitigate climate change when it's actually just the scale at which we've done it that's the problem."

The human cost of shelter life was highlighted by Angel Smith (a pseudonym), 61, who left a Marin County shelter after three weeks due to sleep deprivation from constant bed checks and a restrictive environment she described as feeling like "prison."

For Shawn Pleasants, now an advocate with the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, the potential defunding of permanent housing is a terrifying prospect. "I can't think of anything more damaging than to take people that are on the path to having their lives under control again and place them back on the street," he said, fearing he could be among those evicted. He recalled the soul-crushing reality of holding makeshift funerals for those who die unhoused and unremembered.

With many CoC grants expiring in early 2026 and funding approvals delayed, local jurisdictions face a precarious gamble, unsure if federal support will materialise. Advocates warn that the administration's policy turbulence risks not only increasing homelessness and public costs but also deepening the suffering of the nation's most vulnerable residents.