A renewed government push to build new towns across the UK has been met with stark criticism from the very architects of the postwar programme, who warn the current plans lack ambition on social housing and risk failing those in greatest need.

Warnings from the Pioneers

Senior planners involved in creating towns like Milton Keynes have publicly criticised the government's building drive, stating it shows insufficient commitment to affordable homes. Their analysis suggests new towns have historically provided only a small fraction of the nation's housing needs and are unlikely to deliver at the scale ministers now promise.

Instead of speculative new settlements, they argue, resources should be channelled into strengthening existing towns and cities. Across the UK, redundant land, brownfield sites, and vacant properties offer vast potential for creating well-located, affordable homes. This approach, experts contend, would deliver housing more quickly and sustainably while reinforcing, rather than displacing, established communities.

The Milton Keynes Precedent: A 'Close Shave' for Social Rent

Michael Edwards, an honorary professor at University College London's Bartlett School of Planning, recalls a pivotal moment in Milton Keynes's development in 1967. As the economist for the consultant team, he analysed household income forecasts and concluded the new town needed to build at least half its housing for social rent to achieve its social and industrial mix objectives.

"I was regarded as a bit insubordinate, but my argument carried the day. It was a close shave," Edwards writes, highlighting how pressure from figures like board member Stanley Morton, chairman of the Abbey National building society, favoured owner-occupation. This historical insight underscores the constant tension between public need and market forces in town planning.

A Holistic Vision vs. Developer-Led Schemes

Other correspondents point to the comprehensive success of past developments. Les Bright, who moved to Peterborough in 1981, praises the Peterborough Development Corporation's (PDC) master plan. It provided not just homes, but jobs, cycle routes, schools, libraries, and community workers to help people settle.

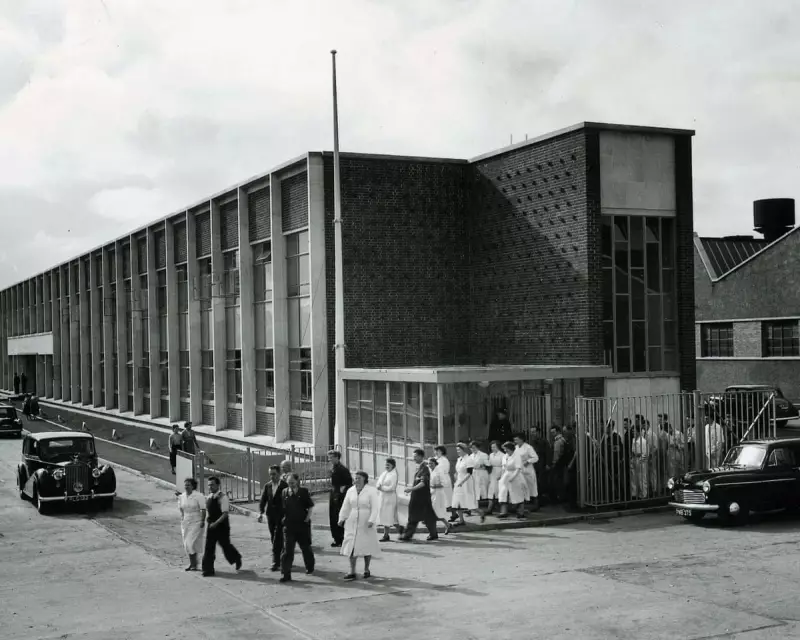

Gordon Davies, a career architect-planner who worked in Skelmersdale, East Kilbride, and Livingston, champions the old development corporation model. He argues new towns must be dynamic engines for new jobs in emerging industries, supported by quality public housing and facilities—not mere massive housing developments for developer profit.

He credits the programme's success to sustained central government support and powerful development corporations that could acquire land at existing use value. Davies, who started in East Kilbride in 1953, warns that without similar political and financial backing, and a focus on community and sustainability, the current plans will not replicate past achievements.

The consensus from these experienced voices is clear: solving the housing crisis requires learning from the ambitious, socially-minded post-war programme, not just building new houses. The priority must be affordable homes within strengthened communities, whether in new towns or old.