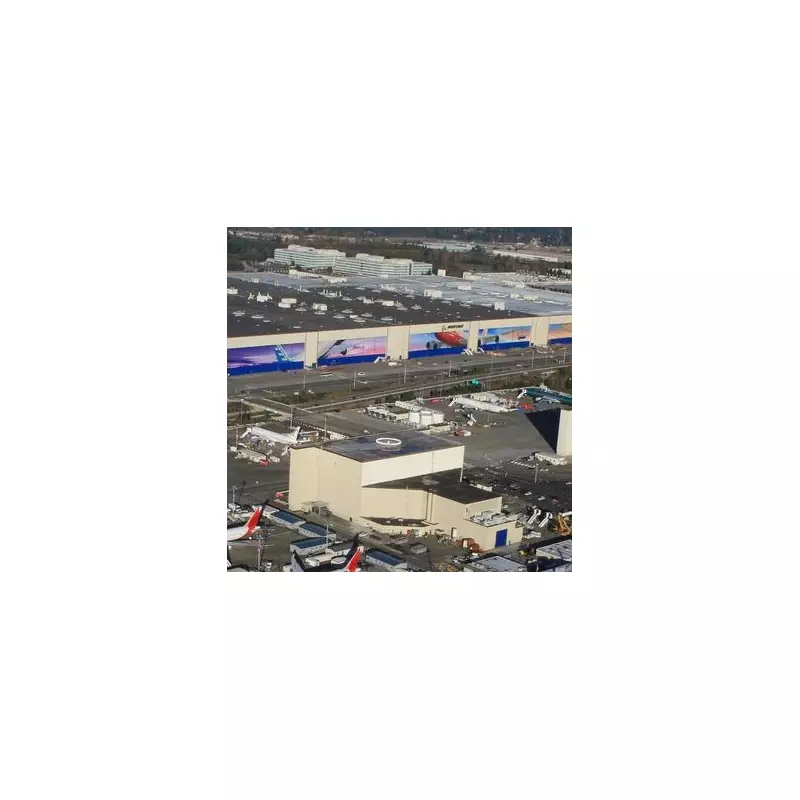

In the world of monumental engineering and aerospace manufacturing, one building stands alone—literally. The Boeing Factory in Everett, Washington, holds the undisputed title of the world's largest building by volume, a staggering complex so vast that it once generated its own indoor weather systems and could comfortably contain the entire original Disneyland resort within its walls.

A Colossal Vision for the Jumbo Jet

The genesis of this leviathan structure dates back to the 1960s, driven by the need to manufacture Boeing's revolutionary new aircraft: the 747 'jumbo jet'. Boeing's then-President, William M. Allen, recognised that existing facilities were utterly inadequate for an aeroplane approximately two-and-a-half times larger than any other passenger plane of the era. After considering sites as far away as California, the company, influenced by chief engineer Joe Sutter, settled on a disused military airfield in Everett, just 22 miles from its Seattle headquarters—a site with a history of building B-17 Flying Fortress bombers during World War Two.

The construction that followed was a feat of breakneck speed and staggering investment. The main structure was completed in just over 12 months, at a cost exceeding $1 billion (around £740 million today)—a sum that reportedly surpassed the entire net worth of the Boeing company at the time. Workers moved 4 million cubic yards of earth, a task so immense it required a dedicated railway line to haul away the spoil.

Mind-Boggling Scale and Internal Climate

The finished facility defies comprehension. Encompassing 98 acres under one roof, with a volume of over 472 million cubic feet, it dwarfs its nearest rival, the Tesla Gigafactory, by 33%. To visualise its scale, the original 85-acre Disneyland in Anaheim would fit inside with room to spare. The building's sheer size once led to a remarkable meteorological phenomenon: in its early days, moisture would accumulate under the 90-foot-high ceiling and form clouds, creating its own microclimate until modern air conditioning solved the issue.

Bonnie Hilory, executive director of the Future of Flight Foundation, aptly calls the factory Boeing's "best product," summarising it in one word: "scale." That scale is managed by an army of 36,000 employees working across three shifts. The site operates like a small city, boasting its own fire brigade, medical facilities, banks, childcare centres, and water treatment works.

Engineering Marvels and Tourist Attraction

Navigating this interior landscape requires innovative solutions. Employees use over a thousand bicycles and several vans to travel through more than two miles of underground tunnels, avoiding disruptions to the sensitive assembly lines above. On the factory floor, 26 overhead cranes glide along 31 miles of rails, moving aircraft fuselages at a painstaking average pace of about one and a half inches per minute. The final painting process for a single 747 uses roughly 454 litres of paint and can take up to a week.

Since opening in 1967, the factory has delivered over 5,000 wide-bodied aircraft. It has expanded twice—in 1978 for the 767 and 1992 for the 777—and now incorporates new structures for robotic assembly and composite wing production for the latest 777X. Boeing anticipates the first 777X delivery by 2027, with 619 orders already on the books as of November 2025.

The factory's wonders are not hidden from public view. It has become a major tourist draw, with 239,579 visitors taking the official tour in 2024 alone, paying $20 (£15) for the privilege. Tourists like David and Georgiana King from Sussex, who visited in 2015 and again in May 2025, return to witness the evolution in technology, such as the introduction of the 787 Dreamliner to the production lines.

The Boeing Everett factory remains a breathtaking testament to human ambition in engineering and manufacturing. It is a place where the boundaries of physical space are continually redrawn, not just to build the world's largest aircraft, but within a structure that is itself a record-breaking monument to industrial might.