Geoscientists conducting research in Northern California have made a startling discovery that could reshape our understanding of seismic hazards along the West Coast. Their investigation has revealed previously hidden fault lines deep beneath the Earth's surface, raising significant concerns that the region's earthquake risk may have been dangerously underestimated for decades.

A More Complex Geological Reality

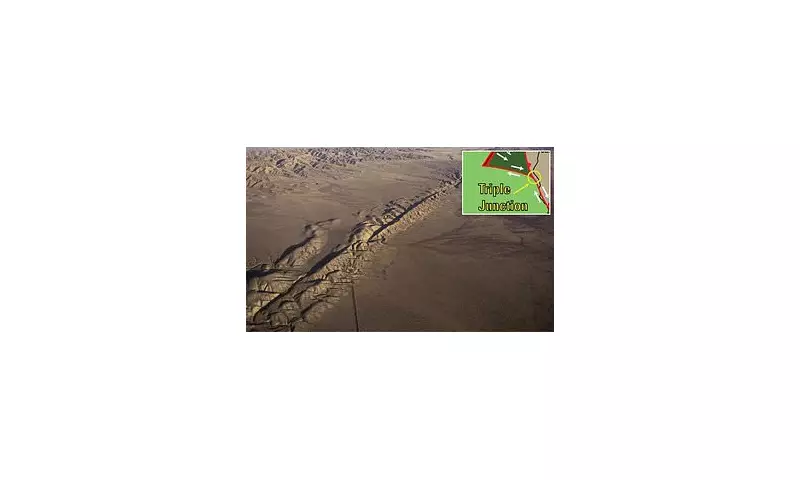

For many years, the Mendocino triple junction was believed to be a relatively straightforward convergence point where three major tectonic plates meet. This area, where the San Andreas Fault terminates in the north, the Cascadia Subduction Zone lies to the south, and the Mendocino Fault extends eastward, has long been recognised as one of the most seismically active zones in the United States, with the potential to generate earthquakes of magnitude 8.0 or greater.

However, new research has fundamentally challenged this understanding. Scientists have now determined that the junction actually consists of at least five tectonic plates or fragments situated deep below the surface. This revelation indicates that the geological structure of the region is far more intricate and complex than previously assumed.

Implications for Seismic Hazard Assessment

The discovery of these additional hidden faults means there may be significant earthquake hazards in the area that current models have failed to account for. Geophysicist Amanda Thomas from the University of California, Davis, emphasised the importance of this finding, stating: "If we don't understand the underlying tectonic processes, it's hard to predict the seismic hazard."

This increased complexity suggests that existing risk calculations for millions of residents along the West Coast may need substantial revision. Because the Mendocino triple junction lies off the coast and influences both the San Andreas and Cascadia fault systems, any changes to the geological model could have widespread implications for earthquake preparedness and building codes throughout the region.

Uncovering Hidden Geological Structures

The research team, led by David Shelly of the US Geological Survey Geologic Hazards Center in Golden, Colorado, employed sophisticated monitoring techniques to investigate the area's subsurface. Using a network of seismometers deployed across the Pacific Northwest, they tracked minute 'low-frequency' earthquakes occurring deep underground where tectonic plates grind against each other.

These seismic events, thousands of times smaller than detectable earthquakes, provided crucial data about the region's hidden geological features. To validate their findings, the scientists compared the observed seismic activity with tidal forces, noting that when gravitational pulls from the sun and moon aligned with plate movements, there was a corresponding increase in small quakes.

Explaining Historical Seismic Anomalies

The new model helps explain puzzling aspects of previous earthquakes in the region, particularly the unusually shallow depth of a magnitude 7.2 earthquake that occurred in 1992. Researchers had long suspected something more complex was occurring at the Mendocino Triple Junction, and this discovery provides the missing geological context.

According to the updated understanding, the southern end of the Cascadia subduction zone features a fragment of the North American plate that has broken off and is being pulled downward alongside the subducting Gorda plate. Further south, the Pacific plate is dragging a mass of rock known as the Pioneer fragment northward beneath the continent.

Revised Geological Understanding

The Pioneer fragment represents a remnant of the ancient Farallon plate, which once ran along California's coastline before mostly disappearing through geological processes. The fault separating the Pioneer fragment from the North American plate runs almost horizontally, making it completely invisible from the surface.

Scientists have compared this newly discovered geological complexity to an iceberg, where the majority of the structure remains hidden beneath the surface. This analogy underscores how much of the region's tectonic framework has remained undetected until now.

The research team's findings suggest that if current models don't incorporate these hidden faults, they may significantly underestimate the amount of stress accumulating underground. This could mean that larger earthquakes might occur unexpectedly, as hidden faults could release energy in ways that previous geological models didn't anticipate.

As David Shelly noted in a statement: "You can see a bit at the surface, but you have to figure out what the configuration is underneath." This research represents a crucial step toward that deeper understanding, potentially leading to more accurate earthquake forecasting and improved safety measures for vulnerable communities along the West Coast.