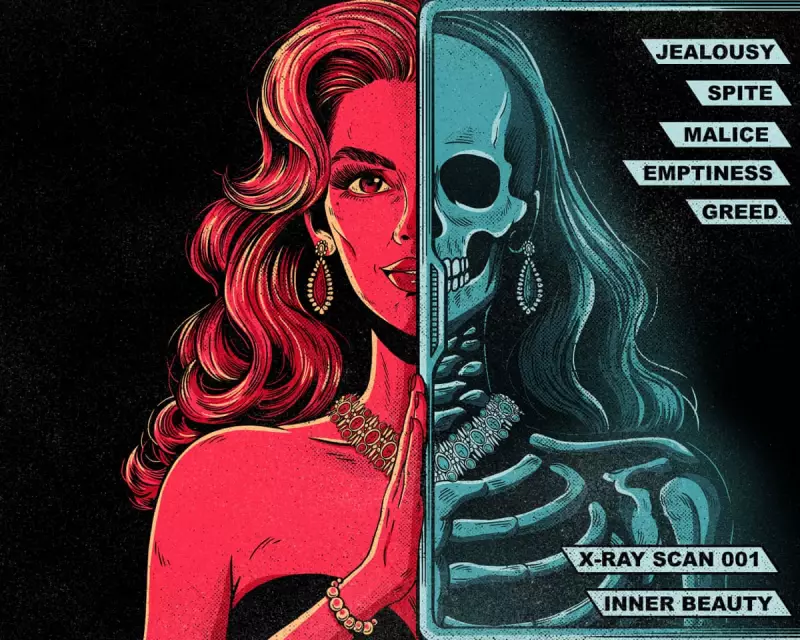

The Myth of 'Ugly Thoughts': Can Inner Morality Truly Shape Outer Appearance?

Our perception of a person's physical beauty is profoundly influenced by our interpretation of their behaviour. But what if we could separate inner and outer beauty entirely? This question lies at the heart of a longstanding cultural debate, challenging the notion that our faces reflect our moral worth.

The Contradiction in Beauty Beliefs

Two conflicting ideas often coexist in popular discourse. On one hand, there is the adage that 'you end up with the face you deserve', suggesting that spiteful or hurtful thoughts can tense and harden facial features over time. Conversely, it is argued that 'no wrinkle can hide inner beauty', implying that true beauty is an energetic, emotional quality unaffected by ageing. These positions cannot both be accurate, as they present a fundamental paradox about how souls and bodies interact.

Consider a simple thought experiment: how can we visually distinguish wrinkles from ordinary ageing in a good-natured person from those of a supposedly 'spiteful' individual? The answer is we cannot, because physical ageing does not correlate with moral character. Yet, these beliefs remain widespread and deeply ingrained in society.

Modern Examples: Politics and Pop Culture

Recent public reactions highlight this confusion. When Vanity Fair published close-up portraits of Trump administration figures, comments flooded social media linking their appearances to perceived evil. For instance, comedian Lisandra Vázquez remarked on press secretary Karoline Leavitt's fine lines, stating, 'If you're evil, you will age like milk', garnering tens of thousands of engagements. Similarly, images of chief of staff Susie Wiles prompted remarks about lying affecting skin or hate causing premature ageing.

In stark contrast, the 2023 film Barbie featured a pivotal scene where a 91-year-old woman is called beautiful by Barbie, with director Greta Gerwig describing it as 'the heart of the movie'. Fans celebrated this moment, praising the beauty seen in women who have lived full lives. This dichotomy reveals that our aesthetic judgments are often proxies for ethical evaluations, as humans naturally seek to make abstract moral concepts visually tangible.

Historical Roots and Cultural Reinforcement

The false association between inner goodness and outer beauty has ancient origins. The Greeks used the word 'kalos' for both, blending ethics and aesthetics. In the 18th century, pseudosciences like phrenology and physiognomy claimed facial features manifested character traits, ideas later weaponised by racists and eugenicists to oppress marginalised groups. Although discredited, this framework persists in Western culture, as explored in Heather Widdows' book Perfect Me: Beauty As an Ethical Ideal.

Moreover, the beauty industry profits from this conflation, promising 'inner beauty' through external products, a point noted by Tressie McMillan Cottom in Thick & Other Essays. Even former beauty editors have perpetuated this myth, highlighting its pervasive influence.

Towards a Solution: Divorcing Inner and Outer Beauty

To find an inspiring solution, we must linguistically and conceptually separate inner and outer beauty. Today, 'beauty' serves as a catch-all term for diverse ideas: the formal beauty of art, physical appearance, and emotional states. This semantic overlap fuels confusion, equating acts like organ donation with cosmetic procedures, which are fundamentally different.

Philosophers argue that true beauty involves disinterest, as Immanuel Kant suggested, or 'unselfing', per Iris Murdoch. Thus, what the beauty industry sells is not beauty but appearance, cosmetics, or hygiene. Attraction relates to desire, while health—such as skin affected by dehydration or stress—is a separate domain. Good people experience stress-induced wrinkles; bad people may maintain flawless skin through wealth and care. Health is a matter of access, not moral obligation.

The 'inner beauty' that contributes to the greater good is simply goodness. Focusing on this virtue won't alter your face, but as the saying goes, no wrinkle can hide it either, offering a more ethical and realistic perspective on human worth.