In a significant development for Colombia's penal system, more than two hundred women with caring responsibilities have been granted early release from prison under the country's innovative Public Utility Law. This legislation, enacted in 2023, provides a pathway for first-time female offenders who are heads of households to serve their remaining sentences within their communities instead of behind bars.

A Miraculous Release from El Buen Pastor

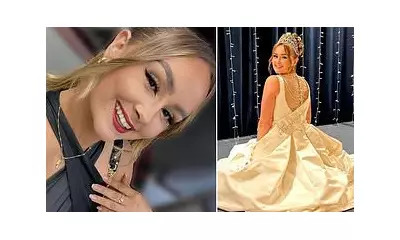

Jennifer Chaparro Pernet became the first woman to benefit from this groundbreaking legislation when she walked out of El Buen Pastor women's prison in Bogotá on 4 May 2024. The 36-year-old mother, who was four years into a twelve-year sentence, described her release as nothing short of miraculous. "I was overwhelmed, I could hardly believe it. I thought, 'God exists, it's a miracle'," she recounted, recalling how she fell to her knees after passing through the prison gates.

Chaparro Pernet's journey to freedom was not straightforward. Despite applying to the scheme immediately after it became law, her application faced rejection three times before finally being approved. Throughout this process, she maintained focus on keeping a good prison record while cautiously nurturing hope for her eventual release.

The Human Stories Behind the Statistics

The law recognises that many incarcerated women in Colombia come from impoverished backgrounds and turned to criminal activities, particularly drug offences, out of sheer desperation to support their families. With approximately six thousand women currently imprisoned in the country, about half are serving sentences related to drug crimes.

Sandra Julieth Cantor, another beneficiary of the law, was released from El Buen Pastor ten months after Chaparro Pernet on 8 March 2025. The mother of one had served five years of a ten-year sentence for drug smuggling. "I was carrying 6,055 grams of cocaine," Cantor explained. "I know the exact figure because it was the 55 that pushed me into a higher sentence bracket."

Both women's stories reveal the complex circumstances that led to their incarceration. Chaparro Pernet began stealing at fifteen when she became a single mother and was later forced to join a gang at twenty-seven, resulting in an eighteen-year sentence that was reduced to twelve on appeal. Cantor turned to prostitution after becoming a single mother at twenty, then moved to drug smuggling when that work disappeared during the pandemic.

Challenges and Limitations of the Reform

While the Public Utility Law has been hailed as a pioneering model for penal reform, campaigners express disappointment with its implementation nearly two years after coming into force. Isabel Pereira, drug policy coordinator at Colombian thinktank Dejusticia, noted: "We were expecting at least half of the 6,000 women in prison would be released within two years, so just over 200 is very disappointing."

Several factors contribute to the limited impact. Inconsistent interpretation of the law by different judges creates a patchwork of eligibility standards across the country. Some judicial officials apply very strict criteria while others demonstrate more leniency. Additionally, lack of awareness among the female prison population presents another significant barrier to wider implementation.

Life After Release: Ongoing Struggles

Women released under the scheme face substantial challenges reintegrating into society. They must complete a minimum of twenty hours weekly voluntary service and report regularly to a judge, though they are not electronically tagged. More significantly, they encounter societal stigma, limited employment opportunities, and broken family ties that complicate their transition to freedom.

Claudia Cardona, a former prisoner who runs the campaign group Mujeres Libres and contributed to the law's development, acknowledges these difficulties while maintaining optimism. "From our experience as women who were incarcerated we believe that, although the number of women who have benefited is still small, every woman who is now free and with her family matters," she stated.

Both Pereira and Cardona emphasise the need for better coordination between government ministries to provide integrated support covering justice, education, employment, and health services. Without comprehensive public policy supporting women after release, maintaining freedom and rebuilding lives with dignity remains exceptionally challenging.

Organisations Providing Crucial Support

The Acción Interna Foundation, established by former actor Johana Bahamón, plays a vital role in supporting women released under the Public Utility Law. Bahamón's organisation focuses on rehabilitating former prisoners through training programmes alongside psychosocial and legal support.

Bahamón's commitment to prison reform began in 2012 after a visit to a women's prison became a turning point in her life. "I thought, you can be deprived of your freedom but you don't have to be deprived of your dignity, and that is my motivation to keep working," she explained. Her foundation now runs drama workshops, prison restaurants open to the public, and comprehensive "second chances" programmes that have assisted thousands of former prisoners.

Chaparro Pernet and Cantor continue to attend courses at the foundation while seeking stable employment. Cantor aspires to become a hairdresser, while Chaparro Pernet simply wants "to provide a stable income for my family." Camilo Higuera, the foundation's communications director and a former prisoner himself, observes: "These are very strong women who are really fighting to leave the past behind. They are the epitome of why you need to give someone a second chance."

As Colombia continues to implement its Public Utility Law, the stories of these women highlight both the transformative potential of progressive penal reform and the substantial work still required to ensure successful reintegration and prevent reoffending among those granted a second chance at freedom.