Human history is littered with dark chapters of ingenuity turned towards cruelty, devising methods of torture and execution designed to maximise suffering. Among these, one technique stands out in folklore for its particularly harrowing and drawn-out nature: bamboo torture.

The Mechanics of a Living Weapon

This gruesome practice, rumoured to have been used in parts of East and Southeast Asia, exploits the natural properties of bamboo. The plant is renowned for its rapid growth and resilience, with some species capable of growing up to 36 inches in a single day. Its combination of speed, strength, and a sharp tip is what made it a feared instrument of torture.

According to historical reports and folklore, the victim would be restrained horizontally, often with the base of their spine positioned directly over a young, pointed bamboo shoot. As the plant grows, it pushes relentlessly upwards, piercing the body. The sharp tip cuts through flesh and continues its journey internally, causing excruciating pain and severe internal damage as it breaks through organs.

Psychological Torment and Historical Claims

The torture is not merely physical. The slow, inevitable growth of the bamboo turns the process into a profound psychological weapon. Victims are forced to confront their mortality in an agonisingly slow manner, with death occurring as a drawn-out process designed to maximise every moment of suffering.

While concrete historical evidence is limited, stories persist. It has been claimed that during World War II, Japanese soldiers employed this method against prisoners of war in Southeast Asia. These accounts, difficult to fully verify, have become part of the dark narrative surrounding wartime atrocities in the region.

Lingchi: Death by a Thousand Cuts

Another infamous method of prolonged execution, often mentioned in the same breath as bamboo torture, is Lingchi, known as 'death by a thousand cuts' or 'slow slicing'. This punishment was used in China, Vietnam, and Korea for the most heinous crimes, such as treason, until it was banned in 1905.

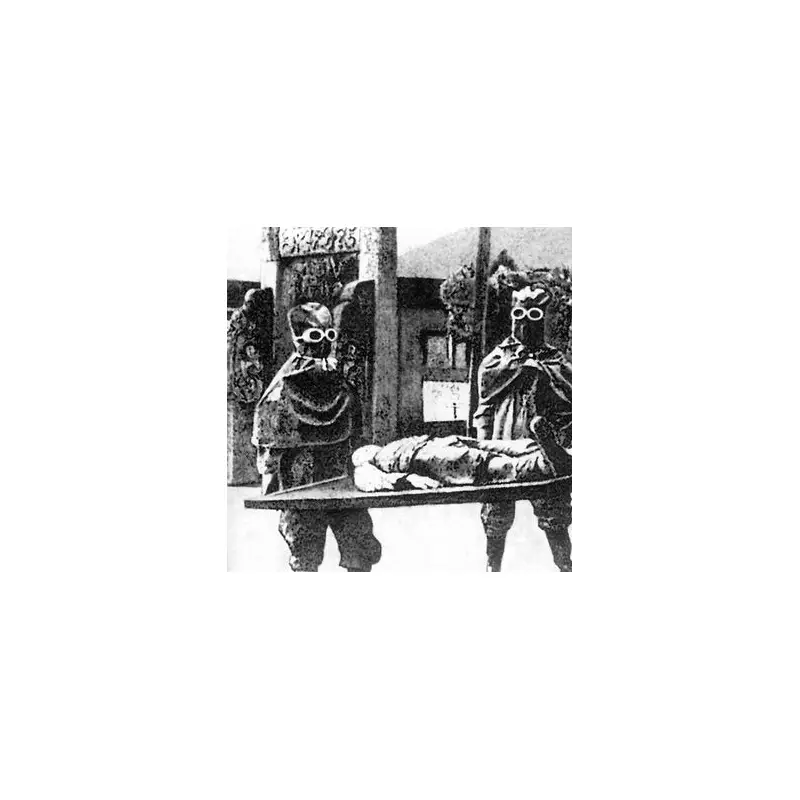

The condemned prisoner would be tied to a wooden frame, often in public. Executioners would then methodically remove body parts with a knife over an extended period until death ensued. The law did not strictly specify the technique, allowing for variation. This punishment served a dual purpose: inflicting unimaginable pain and delivering severe public humiliation. In some grisly accounts, the victim's flesh was reportedly sold as medicine post-mortem.

A stark historical record of this practice is a photograph from 1904 showing the execution of Wang Weiqin, a former official who murdered two families. He was put to death at the Caishikou execution ground in Beijing as the ultimate punishment for his crimes against the family and treason.

These historical practices, from bamboo torture to Lingchi, serve as chilling reminders of the depths of human cruelty. They underscore how methods of punishment have been engineered not just to end life, but to prolong agony and terror, leaving a legacy of horror in the annals of history.