A Surge in Fear Amid a Complex Historical Legacy

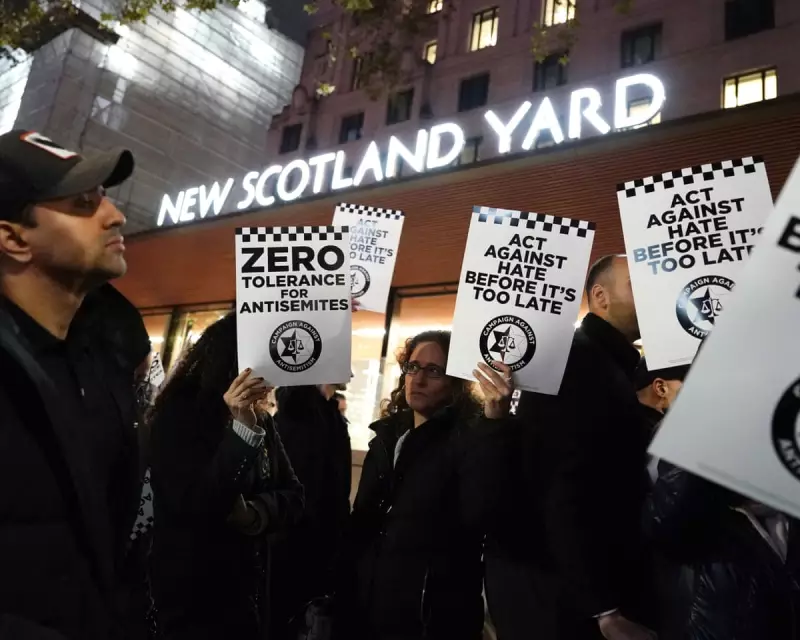

In late 2025, two horrific attacks—one on a Manchester synagogue and another on Bondi Beach in Australia—plunged Jewish communities into a renewed state of fear. These events hardened a perception within the diaspora that a deep-seated historical hatred is intensifying once more. In London, rallies like the one outside New Scotland Yard in October 2023, organised by the Campaign Against Antisemitism, have become a more frequent sight, with communities pleading for more robust police action.

The governmental response often follows a familiar pattern: swift condemnations, ramped-up security, and promises to root out the problem. Yet, fundamental change remains elusive, and the cycle repeats. The sense of crisis in the UK has grown so severe that reports have emerged of the US administration discussing the possibility of granting asylum to British Jews.

Unpacking a Deep-Rooted British Prejudice

To understand the current moment, Professor David Feldman, director of the Birkbeck Institute for the Study of Antisemitism (BISA), argues we must look beyond the Holocaust. Britain's relationship with its Jewish population is centuries old and contradicts the national myth of being a perpetual safe haven.

Jews were expelled from England in the 13th century and barred for hundreds of years, only resettling in significant numbers in the late 1600s. Even then, a fundamentally Christian national identity embedded prejudice in law and public life. It was not until 1858 that a professing Jew could sit in Parliament.

Professor Feldman highlights that widespread, everyday discrimination persisted well into the late 20th century. "My own parents were not allowed to join a golf club as late as 1973," he reveals, noting quotas in private schools and barriers in professions like law and medicine.

The Battle Over Definition: IHRA vs. Jerusalem Declaration

A core complication in tackling antisemitism today is a profound disagreement over how to define it. Feldman describes a "breakdown in consensus," which fuels controversy and anxiety. The debate increasingly centres on Israel and Zionism, particularly since the early 2000s.

This led to the 2016 International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) working definition, which many interpret as classifying certain criticisms of Israel as antisemitic. Feldman, who helped draft the alternative Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism (JDA), argues the IHRA definition was a direct response to the slogan "Zionism is racism."

"The JDA starts from a set of universal anti-racist principles," Feldman explains, contrasting it with views that frame antisemitism as a unique hatred. This clash of principles has created a polarised landscape where name-calling often replaces constructive dialogue.

Data Reveals a Paradox: Rising Incidents Amid Shifting Attitudes

The statistics paint a concerning picture of the present. The Community Security Trust recorded 1,521 antisemitic incidents in the UK between January and June 2025, the second-highest half-year total. A major survey in summer 2025 found 35% of British Jews felt unsafe, a dramatic rise from 9% in 2023.

Yet, Feldman points to a paradox: survey data suggests antisemitic attitudes within the general population are actually diminishing. This raises critical questions about the source of violent incidents. The Manchester and Bondi attackers were inspired by ISIS, a transnational Islamist ideology distinct from the broader movement for Palestinian rights.

Feldman stresses that while some antisemitic expressions have appeared at pro-Palestinian protests, the majority have been peaceful. However, the perception remains that antisemitism is not treated with the same seriousness as other forms of racism, exacerbated by controversies like the police response to chants and the banning of Maccabi Haifa fans in Birmingham.

Moving Beyond Security: Education and a Universal Anti-Racism

In his analysis, Feldman distinguishes between committed antisemites—an ideologically motivated minority—and a wider "reservoir of antisemitism." This reservoir consists of negative stereotypes and assumptions about Jews that are deeply embedded in culture, which people may draw upon casually.

He argues that government focus, under both Conservatives and Labour, has been too narrowly on punishing the former group through security and discipline. "Most often [antisemitism] reflects assumptions and prejudices about Jewish people deeply embedded in the culture," he says. "In these cases, antisemitism needs to be addressed through programmes of education: heightened security and policing is not enough."

Feldman also identifies a blind spot on parts of the left, where an understanding of racism rooted in colonialism can fail to recognise other forms, like antisemitism. He calls for a 360-degree anti-racist approach. "Racism arises in different ways for different groups, but it’s wrong and it’s abhorrent in all cases for the same reasons."

With deadly attacks, persistent abuse, and deep community anxiety defining the current moment, Feldman contends that a re-examination of strategy is urgently needed. The goal should shift from the impossible task of "rooting out" a millennia-old prejudice to realistically minimising and containing it through a combination of protection, education, and universal anti-racist principles.