Seventy years ago, on 5 December 1955, a protest began in Montgomery, Alabama, that would become a cornerstone of the American civil rights movement. The Montgomery bus boycott is now celebrated as a triumphant moment, yet its popular retelling often glosses over the profound uncertainty, immense sacrifice, and years of groundwork that truly defined it. The romanticised fable risks distorting how we understand social change, offering dangerous lessons for contemporary activism.

The Foundation of a Movement: Years Before the Boycott

The story did not begin with a single, spontaneous act of defiance. Rosa Parks was a seasoned activist with two decades of work with the Montgomery NAACP by 1955, not a weary seamstress simply tired from a day's work. "Over the years I have been rebelling against second-class citizenship," she later stated. "It didn't begin when I was arrested." Her stand was the product of a long, demoralising struggle where victories were scarce.

Resistance on Montgomery's buses had been building for a decade. A crucial precursor came eight months earlier, when 15-year-old Claudette Colvin refused to give up her seat and was arrested. Parks herself fundraised for Colvin's defence. While Colvin's case did not spark a mass movement—partly due to how she was perceived by the adult community—it was a vital link in a chain of injustices. Movements are born from accumulation, not isolated incidents.

Courage in the Face of Certain Failure

What made Parks's refusal to move on 1 December 1955 so remarkable was the context of profound pessimism. After years of stands that led to ostracism, injury, or death with little systemic change, Parks had grown doubtful. She had even remarked that summer that she believed there would never be a mass movement in Montgomery. When the bus driver demanded her seat, her action was not a calculated political stunt but a personal line in the sand: to move would be to approve of her own mistreatment.

No one on the bus joined her that evening. She faced the real threat of violence or death. Yet she asked the arresting officers, "Why do you push us around?" This embodies a crucial truth: courage is often the act of persisting without any guarantee of success.

The response was swift but not inevitable. Jo Ann Robinson of the Women's Political Council, which had long organised against bus segregation, mobilised overnight, producing 35,000 leaflets calling for a Monday boycott. A young Martin Luther King Jr., a new father who had lived in Montgomery for just a year, was hesitant when asked to host the organising meeting at his church. His agreement was not a foregone conclusion but a fraught decision with unknown consequences.

The Grinding Reality of a Year-Long Struggle

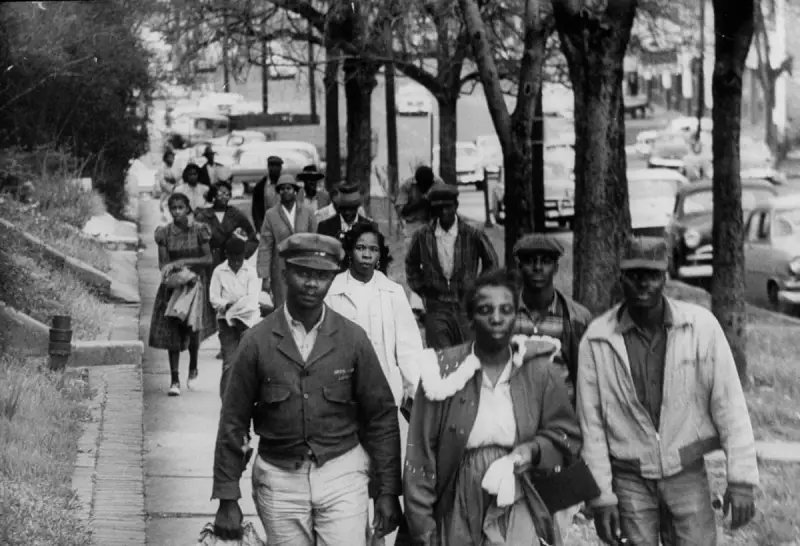

The success of the initial one-day boycott—deemed "a miracle" by King—led the community to continue. This decision ushered in a gruelling 381-day campaign of immense hardship. The boycott's engine was not simply walking but a massively complex carpool system, orchestrated by the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), which at its peak provided 15,000-20,000 rides daily.

The cost was personal and severe. The Parkses lost their jobs and never found steady work in Montgomery again. The Kings' home was bombed just seven weeks in, with Coretta Scott King and their infant daughter inside. Facing intense pressure from their families to leave, Coretta's refusal to abandon the movement was a pivotal moment of steadfastness.

The movement faced fierce opposition. It was labelled "dangerous," accused of communist influence, and compared to the segregationist White Citizens' Council. The city harassed the carpool with hundreds of tickets and indicted 110 boycott leaders. Even the national NAACP kept the disruptive campaign at arm's length.

A Multi-Pronged Victory and Its Enduring Lessons

Ultimate victory came through a combination of tactics. Alongside the sustained boycott, attorney Fred Gray filed the federal case Browder v. Gayle, named for plaintiffs Aurelia Browder, Susie McDonald, Claudette Colvin, and Mary Louise Smith. The US Supreme Court ruling on 21 December 1956 finally desegregated Montgomery's buses.

The true lesson of Montgomery is not about finding the one perfect tactic, leader, or legal case. It is about the power of persistent action amid fear and uncertainty. If activists had waited for a guarantee of success, nothing would have happened. The boycott required acting repeatedly without evidence it would work, building unprecedented systems of mutual aid, and enduring tremendous sacrifice.

As attempts to sanitise history continue, this accurate, complex story offers profound hope. It shows that change is forged by those who, in the words of Vincent Harding, "learn to play on locked pianos and to dream of worlds that do not yet exist," persevering like water on stone until, finally, the rock breaks down.